Fig. 1

With the advent of web applications such as Google Earth, it is a common misconception that aerial photography is relatively new. Admittedly because of these websites it is now more commonplace, but in fact aerial photography has been around since the mid nineteenth century. A Frenchman called Nadar, whose real name was Gaspard Felix Tournachon, took the very first aerial photograph (Fig. 1).

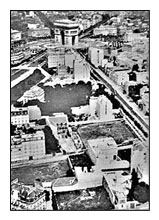

Fig. 2

He was a French writer, caricaturist, photographer and tireless innovator. In 1855 he patented the idea of using aerial photographs in mapmaking and surveying. It was not until 1858, however, that he was able to make a successful aerial photograph, the world's first, from a balloon. The oldest surviving photograph taken by Nadar was of the Arc de Triomphe in 1868 (Fig. 2). His cameras were bulky and he even took a darkroom with him!

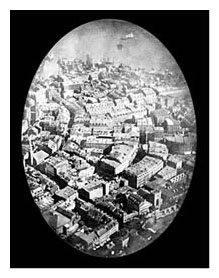

Fig. 3

On October 13, 1860, James Wallace Black, accompanied by Professor Sam King, ascended to an altitude of 1200 feet in King's balloon and photographed portions of the city of Boston. A cable held the balloon in place. Black, the photographer, made eight exposures of which only one resulted in a reasonable picture. This is the oldest conserved aerial photograph (Fig. 3).

In April 1861, Professor Thaddeus Lowe went up in a balloon near Cincinnati, Ohio, to make a weather observation. Whilst in Britain in 1862 The Royal Society began to do the same. Further experiments took place over the next 40 years in Paris, England and Russia. Unfortunately very few of these photographs have survived.

Fig. 4

In 1903, realising the danger involved in the use of balloons, very light cameras were attached to carrier pigeons (Fig. 4). These cameras took a picture every 30 seconds as the pigeon winged its way along a straight course to its home shelter. Pigeons were certainly faster than balloons, but their flight paths were unpredictable.

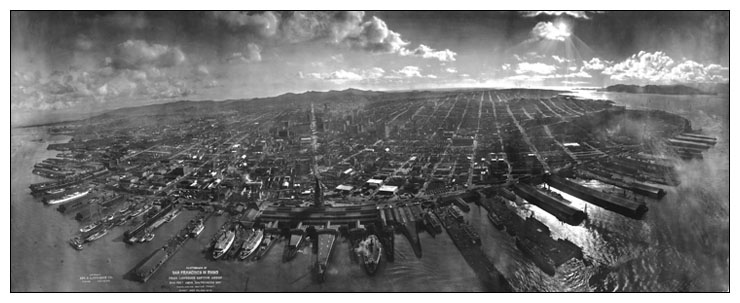

Kites were also a popular method of taking aerial photographs at this time. In 1906 George R Lawrence used a kite to take a panoramic view of the ruins of San Francisco after the earthquake (Fig. 5). He sold prints for $125 each and made a total of $15,000 from just one photograph.

Fig. 5

The military were quick to realise the benefit of using cameras on balloons to spy on what was happening in adjacent valleys and monitor enemy troop movements. But soon it was clear that the aeroplane was the best platform from which to take aerial photographs. Wilbur Wright was the first pilot in remote sensing history that took photographs from an aeroplane. Wilbur's passenger, L. P. Bonvillain, on a demonstration flight in France in 1908, took the first photograph from an aircraft.

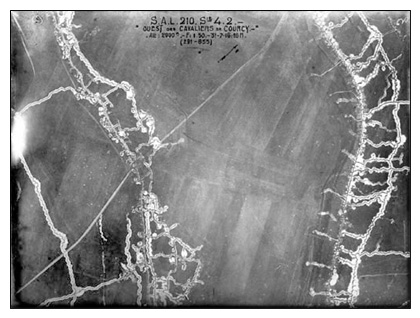

Fig. 6

As with most technological innovations, major advances were made with the onset of war. The First World War saw the introduction of roll film to replace the glass plates. Aircraft were also adapted and designed to maximise coverage and optimise quality, by being fast and stable. Early in 1918 French units were printing as many as 10,000 photographs a night during periods of peak activity. The UK, US and Germany all had sophisticated aerial reconnaissance units, and many technical hurdles had been overcome. It was however not without its problems; from above, identifying one soldier from another was not easy. One time a German observer indicated that an English unit was running around in great disarray and appeared to be in a state of panic. The English were playing football. Tens of millions of photographs had been taken by the end of the war in 1918 (Fig. 6).

Following the war many companies were set-up to use the newly found skills and techniques for more peaceful purposes, namely mapping. Some of these companies are still going to this day, in the UK, US and Germany.

At this time the UK was well mapped and aerial photography was not taken too seriously as an aid to mapping; however it proved invaluable in poorly mapped parts of the world that were at the time under British control. For example Hong Kong was photographed in 1924. From 1930 Germany started to map the country at 1:25,000 scale, and the towns at 1:10,000 scale. From the 1930 aerial photography had become relatively commonplace and aerial surveys were regularly practiced. In 1934 The American Society of Photogrammetry was founded to advance the field of aerial photography.

The rate of technical development and innovation increased once again during the Second World War and the importance of aerial survey was by now appreciated in the UK. Following the conclusion of the war in 1945, unlike after the First World War, the Air Force was put to work in the UK before demobilisation. The aim was to capture the entire country at six-inch scale (1:10,560), with the cities at higher scales. It was called Operation Review or Revue.

Fig. 7

In the 40s and 50s huge surveys were undertaken by the US, UK and Russian military, including huge areas of mainland Europe, for example the DDR and Poland. Much of this was done in secrecy because of security issues and the onset of the Cold War. In the 1950s the major post-war Government-sponsored projects and secret Military surveys (Fig. 7) came to an end except for occasional urgent situations such as the flood disasters of 1948 and 1953, and the Aberfan tragedy. Of course, the Military continue secret reconnaissance probing to this day.

Aerial photo surveys carried out on behalf of local and central government, utilities and large civil engineering projects became routine as well as essential. These were done by commercial organisations during the 60s, 70s and 80s. During the 80s the transition was made from black and white film to colour film. Throughout this time many of these surveys were often used on a 'one-off' basis, i.e. they were flown for one client who had one use for them. Resale of the photographs did happen, but, it was still a relatively specialist subject, so it was not big business. Many films and boxes of contact prints languished in dark rooms deep within local authorities. Relatively little improved in this time.

It was in the mid to late 90s that the resale value of aerial photography was really acknowledged. The shift was made from the survey companies carrying out a survey on behalf of a client, to the survey company actually investing in speculatively acquiring photography and making a commercial business from selling the photos multiple times. Aerial photography had entered the digital age. It was now easy to scan and reproduce the photos, and therefore distribute them as large digital seamless mosaics. The range of products and applications of photography also increased, Digital Elevation Models, orthophoto and 3D building modelling became far easier to produce and at a lower cost. As technology improved so did the scale (and therefore resolution) of the photos being taken. The users wanted to see more and more detail.

In 2004 the first large format digital aerial survey cameras became commercially available. The take up of these cameras was swift in the UK and Europe. By 2007 the majority of aerial photography in the UK was taken digitally. These cameras are often fitted with GPS and Inertial Measurement Units, which improve the accuracy and time to create the orthophotos.

Technology is going to continue to improve and so will the quality of aerial photography. Web portals such as Google Earth are making the photography (as well as other GIS data) available to the general public, globally. Who knows where the next ten years will take us?

|